Pedestrianising Claudelands Bridge, permanently

Forget traffic chaos, we've had a multi-modal paradise for several weeks

“Chaos in the city” was the headline, but for people walking and biking, the trip over Claudelands Bridge has been anything but.

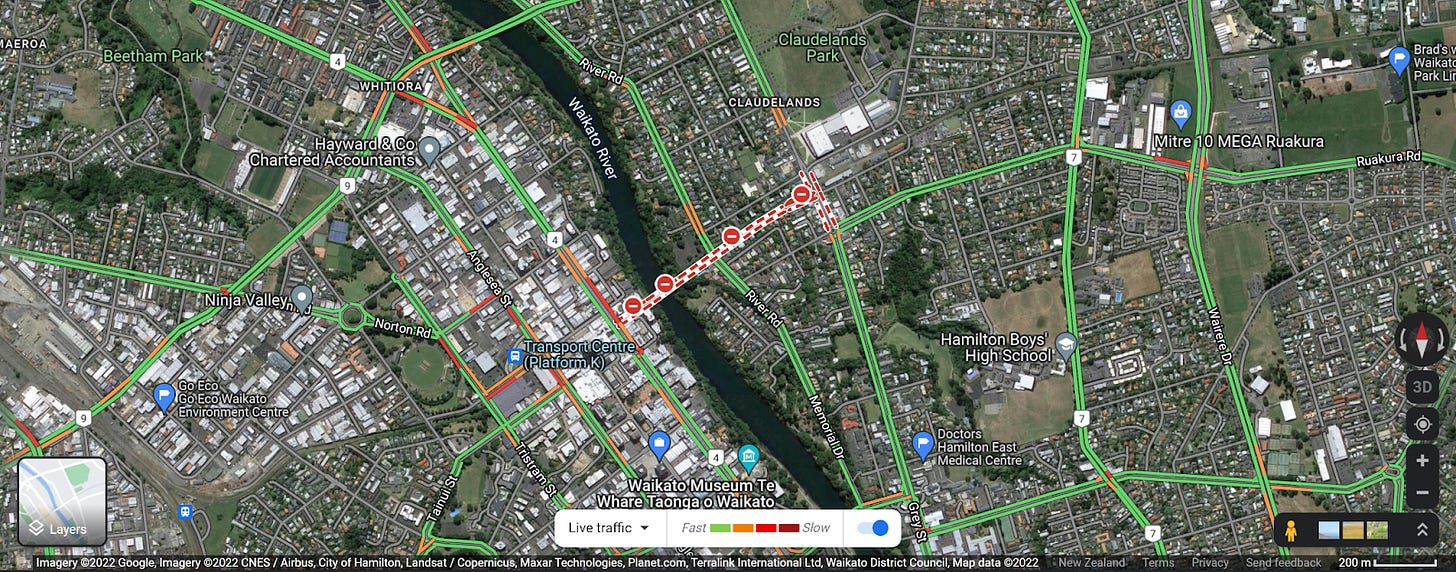

In case you missed it, safety improvements in Claudelands East began on Monday 10th October. Two intersections are closed to cars for four to five weeks - the Claudelands Road/Grey Street intersection and the Heaphy Terrace/O’Neill Street/Brooklyn Road intersection.

People walking or biking can still access the area, which means they're breezing through a multi-modal paradise, no longer competing with impatient cars who don't care for the sharrows or the 30km/hr speed limit.

People driving have experienced delays to their trips, which the article predicts “would remain this bad for the entire four weeks of work”. Stuff frames the “chaos” as being caused by the road closures, however, the fact that the bridge and intersections had been closed for an entire week before anyone thought to complain suggests something else is causing the traffic. I would wager this “something” is the end of school holidays and the mass return to 8 am car trips to school and work.

As a transport planner, I think traffic is one of the most misunderstood and most frustrating concepts to see discussed in public forums. It tends to be portrayed as this inelastic truth that we cannot alter.

The reality is very different, and we have the ability to manipulate traffic to make our city a more pleasant place to live - and a more climate-friendly one.

At first, this might sound unbelievable, but one way to do this is by turning Claudelands into a car-free bridge permanently, leaving access open for:

People walking, biking or on micro-mobility

Buses travelling in the peak direction

Emergency services

It seems counterintuitive that closing the bridge would reduce traffic overall, but the concepts of induced demand and traffic evaporation can help explain how this works.

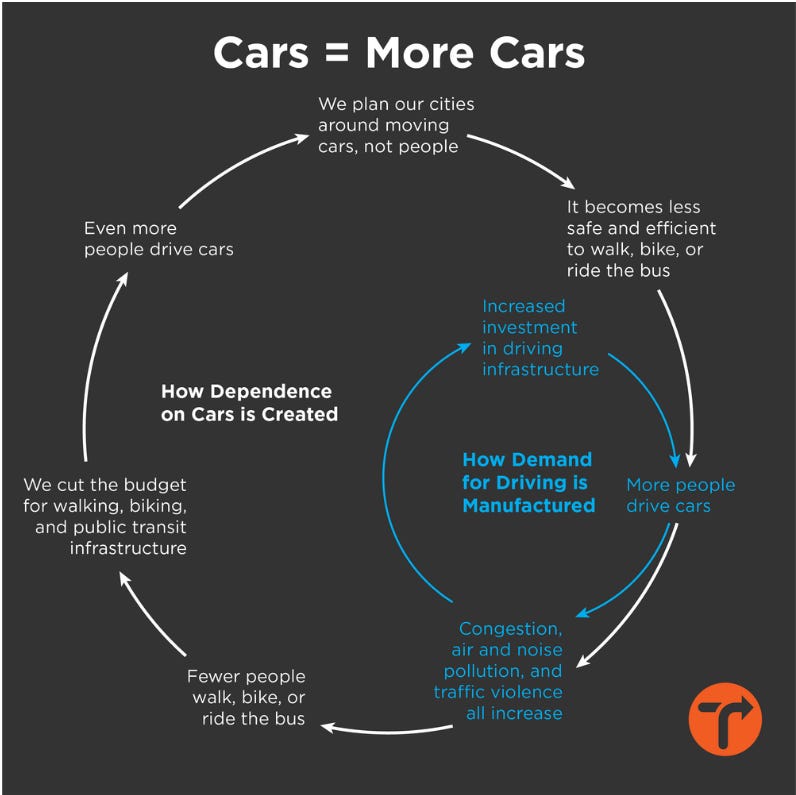

Induced demand

Induced demand describes the phenomenon where increasing capacity for cars on our roads increases the number of people driving on that road. The more money and space we allocate to making driving easier, the more attractive it becomes to drive compared to any other mode so of course, more people will drive. Over time this means roads are clogged up with traffic again, so we add more lanes and the cycle continues.

This explains why when a lane is added to a busy road, traffic never seems to get any better. We’re still stuck in traffic, just with some extra cars beside us. If you’re still struggling to imagine this, picture Auckland: lanes have been added to the motorway over the last decade, but has traffic gotten any better?

The diagram below shows how induced demand works on a city-wide scale.

Traffic evaporation

If induced demand describes how we encourage more people to drive, traffic evaporation describes how we might achieve the opposite.

When a road is closed or a lane is reallocated to a different use (e.g. when a bus-only lane is created) some of the traffic is described as “evaporating”. This is because the overall number of cars in the area goes down in response to the closure or reallocation. This evaporation doesn’t usually occur straight away and there is typically an adjustment period of 2-3 weeks. However, after the adjustment period in most cases, travel times return to normal and congestion decreases. We saw this during the Innovating Streets trials of 2021 - there was no real change in the average travel delay in the streets surrounding Rostrevor during the trial period.

This happens because humans are pretty smart. Once we’ve sat in traffic on our commute for a day or two we all make little decisions that add up and allow traffic to evaporate.

Over the next few weeks in Claudelands some of these decisions might look like:

Using Google Maps to select the route with the least traffic

Driving to Sonning Car Park, or one of the surrounding streets and walking over the bridge instead of driving into town

Choosing to make non-essential trips outside of peak traffic hours

Working from home to avoid the traffic completely

Walking or biking into town instead of driving

Carpooling for the school drop-off with other parents or sending the kids on the bus

These decisions add up and mean we can expect traffic to decrease by around 11%. This means that after the adjustment period we can expect traffic to flow about the same as before the closure, or even a bit faster. Sadly, by the time we start to see this benefit, the safety improvements will be finished and the roads will open back up to cars for business as usual, just with a few more cycle lanes.

Removing cars from Claudelands Bridge in the long term would give us a chance to take meaningful action towards our city’s climate change goals. If we want people to choose low-carbon modes, we need to make them the easiest, safest and most convenient choice. A car-free Claudelands Bridge would achieve this, especially as Waikato Regional Council strives to improve bus frequency and Hamilton City Council rolls out new biking and micro-mobility infrastructure, giving people genuine choices in how they get around our city.

Kiri Crossland is a transport planner, a board member of Go Eco, and a Master of Environmental Planning student at the University of Waikato.